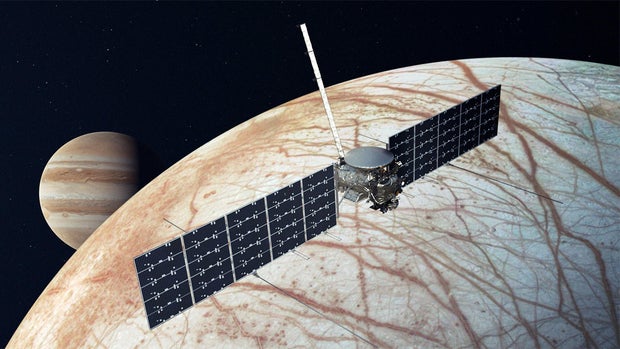

After an exhaustive review of suspect transistors in NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft, NASA managers have cleared the probe for launch next month as planned on a $5.2 billion mission to find out if a suspected sub-surface ocean on Jupiter’s icy moon Europa is a habitable environment.

The transistor issue cropped up in May, raising fears the scope of the Clipper’s mission might have to be reduced or the flight delayed for costly repairs.

But the review showed the transistors in question will, in effect, heal themselves during the 20 days between the high radiation doses the probe will receive during each of 49 close flybys of Europa, all of them deep in Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field and radiation environment.

NASA

In addition, onboard heaters can be used as needed to raise the temperature of affected transistors, improving the recovery process.

“After extensive testing and analysis of the transistors, the Europa Clipper project and I personally have high confidence we can complete the original mission for exploring Europa as planned,” said Jordan Evans, Europa Clipper project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The solar-powered Europa Clipper, one of NASA’s most ambitious planetary probes, is a “flagship” mission designed to make multiple close flybys of Europa to learn whether a subsurface salt water ocean beneath the frozen world’s icy crust could host a habitable environment.

If habitability can be confirmed, “just think of what that means, that there are two places in one solar system that have all the ingredients for life that are habitable right now at the same time,” said Curt Niebur, Europa Clipper program scientist at NASA Headquarters.

“Think of what that means when you extend that result to the billions and billions of other solar systems in this galaxy. Setting aside the ‘is there life?’ question on Europa, just the habitability question in and of itself opens up a huge new paradigm for searching for life in the galaxy.”

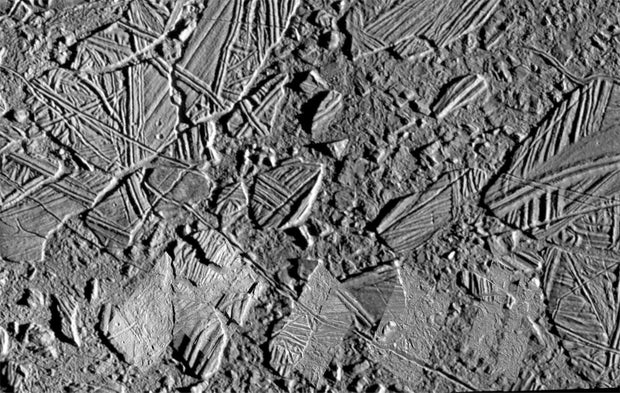

Discovered in 1610 by Galileo, Europa has been studied by NASA’s Voyager probes and, much more extensively, by the agency’s aptly-named Galileo orbiter in the 1990s, which made a dozen close flybys.

The spacecraft discovered that Jupiter’s magnetic field was disrupted around Europa, implying an electrically conductive fluid deep within the moon. Given Europa’s frozen crust, the most likely explanation is a sub-surface salt water ocean, kept warm by tidal flexing, the repetitive squeezing by Jupiter’s enormous gravity as the moon swings through its orbit.

NASA

The Europa Clipper is not designed to search for signs of life on or below Europa’s crust. But confirming the presence of a hidden sea and determining its habitability would be a major step forward in the search for places in the solar system and beyond where life, as currently defined, could exist.

“This is an epic mission,” Niebur said. “It’s a chance for us to explore not a world that might have been habitable billions of years ago, but a world that might be habitable today, right now,”

“A chance to do the first exploration of this new kind of world that we’ve discovered very recently called an ocean world, that is just totally immersed and covered in a liquid water ocean, completely unlike anything we’ve seen before. That’s what Europa Clipper and her team are going to unveil for us.”

Scheduled for launch from the Kennedy Space Center on Oct. 10 atop a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, the spacecraft will first fly past Mars in February, using the red planet’s gravity to send it toward another velocity-boosting flyby of Earth in December 2026.

Only then will the Europa Clipper be traveling fast enough to head out into deep space on a trajectory to Jupiter. Even so, the probe won’t reach its target until April 2030, using its thrusters to brake into an initial orbit around the giant planet.

Five months later, the first in a series of close flybys of several moons will be needed to set up the first close encounter with Europa in the spring of 2031. During two science campaigns running through 2034, at least 49 close flybys of Europa are planned, including passes as low as 16 miles above the moon’s frozen surface.

The mission was progressing toward launch when engineers were alerted in May to a potentially serious problem with transistors used throughout the spacecraft. Similar components were found to fail at lower radiation doses than expected.

The radiation environment around Jupiter is powered by the planet’s titanic magnetic field, which traps and accelerates electrically charged particles from the solar wind and the volcanic moon Io. The radiation environment in the vicinity of Europa would kill an unprotected astronaut in a matter of hours.

As a result, Europa’s flight computer and other key components are protected in a radiation-resistant “vault.” Radiation “hardened” components are used throughout the spacecraft. But test data from the manufacturer showed similar components were failing at lower radiation levels than the Europa Clipper will experience.

But after months of testing, engineers concluded the spacecraft can complete its mission with no major modifications.

“We completed extensive testing to validate the transistors on the spacecraft,” Evans said. “We ran tests 24 hours a day over the last four months at multiple locations. We simulated flight-like conditions to illuminate any issues that the transistors might have over our four-year science mission across the variety of applications we have on the spacecraft.

“We put these representative transistors into these environments, irradiated entire circuits to see how the system behaves. … We replicated that transistor self-healing, or annealing as it’s called, that occurs by heating them to room temperature while they, essentially, (are out of) that intense radiation environment as we go around each orbit.”

Based on the results, he said, “we’re ready for our final launch preparations and reviews. We are ready for Europa.”