The original idea, I admit, was mine, I take responsibility for that, and not only for that.

At a small dinner party my wife Helen and I hosted back in November, it seems like a long time ago now, several friends, new friends, not people we know very well, were complaining about how much time they spent on their phones, they were lamenting with early-middle-aged fatalism that their phones had long since been getting in the way of their reading real books, of their conversations with their children, of their exercise routines and their work, I remember that what struck me at the time was that anyone at all was still willing to complain out loud, even fatalistically, about a battle between us and our phones that everyone else already agreed had been so completely lost that the defeat was no longer even mentioned anymore, and it was then that I had and voiced my ill-considered and ultimately disastrous idea.

‘We should have a phoneless party,’ I said to the couple consisting of new friends as well as the couple – the Charlies we call them, a man named Charlie and a woman named Charlie – who counted as older friends, I looked at my wife (we are still married) and said: ‘Why don’t we have a phoneless party, a phone-free party? We could have it on New Year’s Day? A day free of phones?’

I suggested that on January 1st people could come over in the morning, for brunch, and then stay all day, hanging out and listening to records in our living room, and/or hiking or (if there was snow) sledding in the park, before returning to the living room and the fire, and in deference to our new friends’ enthusiasms – one of them, the woman, Sandra, was and I suppose still is a psychedelic entrepreneur specializing in little color-coded pills delivering different quantities of psilocybin powder representing everything from the most modest microdose up to a full-blown mind-rearranging trip – I also suggested that the guest room upstairs could function as a chill-out room, if that was still the term, for people who were tripping and didn’t feel like engaging with the whole living-room social experience, and if there were MDMA-takers among our guests at the phoneless party these too could be accommodated, in their own room if they liked, for example in my and Helen’s bedroom, and anyway the whole scene and event could function as a be-in (a term I knew hadn’t been current for fifty years or more, and used facetiously) of undistracted company and recreation facilitated by, among other things, the absence of our phones that were otherwise (not that I said this part, that would have been unnecessary) all the time breaking up our attention into scattered meaningless fragments of amusement and dread.

‘It’s like they do this at plays and concerts these days, sometimes,’ said Sandra – such a wholesomely pretty white woman, with broad, vaguely rural features, and immaculate peaches-and-cream skin, that she might have been the model for a fascist propaganda artist of some kind – who’d already warmed to the idea. ‘They make you hand over your phone.’

‘Exactly,’ I said. ‘We have this old wooden trunk in our bedroom. I could lock the phones in there.’

Helen too seemed to like the idea, possibly because of the prospect of our taking a bunch of drugs with friends as if we were still young, not so long ago I’d joked to her, when she’d been pressing me to take edibles before a movie, that youth was about telling yourself you really needed to stop doing so many drugs, while middle age, as it turned out, was about telling yourself you really needed to start taking more drugs, I should mention that Helen and I don’t have any children, only a cat named Harriet, so for us there really was no excuse not to spend more of our weekends becoming wiser, happier, more sexual beings by way of appropriate doses of mushrooms, MDMA, weed, et cetera, and in truth it was usually me who dragged his feet before this prospect, I suppose I was afraid that weed or mushrooms would only sharpen my attention to the horrors of the world, both the discreet grinding horror of collapse and the more spectacular horrors of state-led or freelance massacres, not to mention ‘natural’ disasters, and on account of these hovering intimations I feared I might not have such a good trip on mushrooms or edibles at all, meanwhile as for MDMA I knew that rolling (was this the term anymore?) on molly (was that the term either?) couldn’t do much for me so long as I continued, like approximately half the people I knew, to take my daily SSRI.

‘If we’re going to do this,’ Helen said brightly, ‘we should send out an invitation soon. That way people can arrange babysitters.’

Helen I won’t physically describe, she is a beautiful woman with little beside kindness in her eyes, but I find that once you are married (in my sole experience of the phenomenon so far, many of my friends, having been married at least twice by now, would be better qualified to say) you don’t really see the person anymore after a while, instead you merely recognize them, they become so familiar in their features as almost to forfeit their features completely, a little bit as if they were your own feet or something, which you never pause to study or even to see before pulling on your wool socks.

‘Oh yeah – great idea – we can hire a dog-sitter,’ male Charlie was adding to the conversation, being, with female Charlie, the owner of a large, beautiful and needy Great Dane by the name of August, a name I’m sure I’ll remember for the rest of my life.

The dinner party in question took place on Friday November 18th, I know this because I can still see in my Gmail that it was on Tuesday November 22nd that I sent out the invitation, to more than twenty friends, to a phone-free New Year’s Day party that was to get underway with brunch and last until people felt like going home, hopefully after dark, not that the arrival of dark (as the email didn’t need to say) indicated such a long day when the days are so short not even two weeks past the solstice, and our house lies so close up against the foothills to the west of town, that the sun will have set, on early-winter days, before 3.30 in the afternoon.

The big-box liquor store out on Kiowa opens at 8 a.m. 365 days a year, so the sign posted on the sliding front door tells you, and already at 8.30 a.m. or so on New Year’s Day, when I went out, on behalf of our guests, to buy some gin and mezcal, for brunch-time Bloody Marys and Bloody Marias respectively, it was apparent that this was an exceptionally windy day, in fact when I was driving back down Arapahoe with a passenger seat full of booze I discovered that the traffic lights had been knocked out by the wind, so that cautious drivers nosing out into the intersection had to take their turn, before accelerating, as if invisible stop signs stood at the corners of the streets rather than the dead sentries actually posted there.

Another way that I try to beat back any depression is with regular exercise, and so, after depositing the liquor back at home, I drove out to the open space south of town to get in a short run, was the idea, before our guests arrived, I was thinking that a jog through the fields near the creek, where trees were sparse, would be safer than running through the woods where a branch torn off a ponderosa by the crazy wind might well club me to the ground or worse.

Having earlier had to close my eyes against flying grit in the liquor store parking lot, when I got to the trailhead, before getting out of my car (an EV for what it’s worth), I put on the wraparound sunglasses that ordinarily I only wear while biking, in order to shield my eyes, as I ran, from the scouring dust in the air, but even so, once I was ‘running’, or really stumbling, over the trail toward the mountains, shoved by the buffeting winds at my back, I didn’t even make it a quarter of a mile before turning around and heading back to the car, out in the fields south of town there was no one else to see at 9.30 a.m. on a New Year’s Day characterized so far by merciless winds of (as I later learned) 80–100 miles an hour, except for a young woman, no doubt a professional dog walker, walking four dogs on separate leashes through the pummeling air, and I was concerned enough for the young woman’s unprotected eyes – she herself had no sunglasses on – that I offered her my wraparound sunglasses only to have her look at the author of this gesture as if he weren’t at all the good man I was meaning to be but only a strange one, anyway not only did the dog walker refuse the gift of the wraparound shades but of course there was nothing I could do for the dogs and their eyes, and I’ve often wondered since that day, with a curious persistence, whether the eyes of any of the four dogs might have been injured by what I guess I’ve already called the scouring dust in the air, when I wonder this I always think also of the crazed ticking sound of the dry grasses rummaged or ransacked by the wind, these grasses making a sound, it seemed to me at the time, of so many wristwatches (not that wristwatches are worn anymore) having gone insane all at once.

Back at home I asked Helen whether I should maybe text our friends and advise them to venture out only with ski goggles or wraparound sunglasses, if they were still coming over for our phoneless party, that is, but sensibly she insisted: ‘These are grown-ups, they can take care of themselves,’ and indeed none of our guests arrived at our house complaining of any injured eyes, it was only a few days later that we learned that Sophie and Tim hadn’t made the party because Sophie’s right eye had been hit by a particle of glass flung through the air and she and Tim had therefore spent the day at one of the urgent-care outfits in the strip malls east of downtown.

For brunch we’d laid out in the kitchen an array of bagels and bagel trimmings as well as vegan and merely vegetarian spreads, we’d also set up a station for Bloody Marys and Marias, even though a number of people wouldn’t be eating anything, or drinking beverages other than water, the better to absorb the psilocybin and/or MDMA they planned on taking.

‘Are you going to take some molly?’ Helen asked me hopefully before the first guests had arrived, and I reminded her that MDMA was unlikely to have any effect on me, given my course of antidepressants.

‘Oh right,’ she said. ‘You could take mushrooms?’

Rather than reiterate my fear of having a bad trip if I were to take drugs at any time during the remainder of the twenty-first century, I just said that it seemed to me there ought to be at least one totally sober person at the party, in case of any eventualities.

‘What eventualities?’ Helen wanted to know.

‘I mean,’ I said, ‘if we knew what they were . . .’

‘We might as well have had kids,’ she said, not unpleasantly, ‘if you were going to be this square.’

‘No one says square,’ I said.

‘I’m going to take some drugs,’ she went on, adding that she might take both some psilocybin and some MDMA.

‘I think the kids used to call that candyflipping.’

Sarcastically she said: ‘Like at Burning Man in 2003?’

For the shortest segment of a moment I wondered why someone should speak of the futuristic year of 2003 as if it were decades ago.

‘I think I’ll also keep my phone on me,’ I said. ‘Just in case.’

‘But it’s a phoneless party,’ Helen protested.

By noon or maybe 12.30 p.m. we’d welcomed into our house all thirteen of our guests through the back-patio door or else the front door, while I held whichever door it was against the wind, probably every one of the guests remarking as they took off their coats and boots about the absolutely crazy, totally insane wind, a few of them joking that the new year was off to an ominous start, before obediently handing over their phones which I then set down inside the mahogany trunk in our bedroom, more than a dozen years earlier I’d found the trunk in an antiques market in Buenos Aires and liked it so much that I’d had it shipped back to me in the States, the only real souvenir of a trip that otherwise I now hardly remembered, except to know I’d taken it with my girlfriend at the time, she was someone I was these days hardly ever in touch with unless one of us had to let the other know that some person or animal we had in common had died, once upon a time we’d gone to Iguazú Falls in the north of Argentina and watched a river as broad as an interstate collapse below us into a cataract of steam, small swallows somehow darting in and out of their invisible nests behind the vertical sheets of deafening water.

It can’t have been 2.30 p.m. yet before the party had sorted itself out into sober-enough people listening to LPs in the living room, and MDMA-takers in our bedroom, and elsewhere – outside in the yard, or upstairs in the guest room – people tripping hard enough on shrooms and/or molly as to want a little privacy, meanwhile I saw Helen go off, I didn’t know where, with Rachel and Dan, admittedly a very attractive couple, looking a little wistful and even perhaps guilty as she went, not that we hadn’t already discussed and both signed off on the possibility of (what to call it?) some extramarital activity one of these days if the spirit moved us, a possibility that didn’t seem very probable to either of us but that we’d allowed for anyway, now that Helen was leaving my sight it seemed to me a more melancholy fact that nothing was likely to happen for her than it would have been had a threesome actually promised or threatened to take place.

In the living room, after making sure our guests all had the drinks and/or drugs they required, I put on a Sun Ra record which had seemed adequately psychedelic for the occasion but that, once it was spinning, sounded dirge-like to me with its disorderly trudging horns, so that before the first track had even concluded I turned the stereo over to my discreetly hulking friend Alex, a college friend who’d played tight end for two years, Alex had brought over a Boards of Canada vinyl reissue for the occasion, in fact it was a record that (in CD format) I’d listened to a lot back when the techno or IDM of the first George W. Bush administration had sounded to my ears like the front edge of now.

Against the seething aural wallpaper of the – to my ears – vaguely dysphoric and minatory clicks and bleeps and swells of what I believed to be Boards of Canada’s second album, male Charlie was soon telling a humorous story about a French friend of his and female Charlie’s, a medical anthropologist, who’d recently visited them here in this college town at the edge of the Rockies and, in spite of his – the anthropologist’s – travels throughout much of Europe, Asia and the Middle East (three regions of the globe I myself generally did my best not to think about, let alone visit), found himself freaked out by and almost frightened at the – to his French mind – very large and aggressive squirrels of central North America.

I was going to ask whether the French medical anthropologist hadn’t even ever been to New York City or someplace like that, on some previous trip to North America, because didn’t they have the same kind of squirrels there, of more or less the same very frightening dimensions? but, no need, this very same question was presently posed by a guy named Rob or Doug who’d accompanied Sandra and her husband to the party, I never heard from or about this generic male personage again, it was a bit like having a joke about some current event occur to you and placing it into the search bar of Twitter or X, or whatever the doomscrolling microblogging platform was called these days, only to confirm that dozens if not hundreds of other people had already hit on the very same joke as you and there was thus no need for you yourself to make it.

‘Yeah, I know, he’s definitely been to New York,’ said male Charlie about the squirrel-menaced Frenchman. ‘I guess the squirrels weren’t the main thing he noticed there.’

Male Charlie, a tall and very handsome (I guess we have a lot of good-looking friends) half-Asian environmental consultant with a man bun, made this unobjectionably ordinary remark in the same tone of affable, accommodating decency that tends to characterize everything he says, and it occurred to me that I’d always had some difficulty talking to this Charlie for the simple reason that, not least because he was and no doubt still is in such good physical as well as mental shape, nothing at all seemed to be wrong with him, I’m not sure that I was even always very good at meeting his eyes.

Talk of the antic and threatening squirrels of North America, to which all of us were nevertheless totally accustomed, led in a moment to discussion of a more problematic local rodent, the prairie dog, whose colonies were often being flooded by county officials with poison gas so that the Hamas-like network of their tunnels beneath the fields couldn’t be enlarged in such a way as to ruin the prospect of successful irrigation for local ranchers enjoying grazing rights on such publicly owned land.

‘I guess they’re doing what they have to do,’ said Sandra’s husband Christopher. ‘But you can’t help feeling bad for them.’

‘Who, like, the prairie dogs? Or the poisoners?’ Sandra asked.

‘I mean I guess both,’ Christopher said. ‘Definitely both.’

Personally, I had attended a town-board meeting to speak up and object to the gassing of the prairie-dog colonies, suggesting that it was on the contrary ranchers and their cows who would do better to leave the land, after all the contribution of prairie dogs to climate change is surely negligible, something that can by no means be said of methane-emitting cattle, not to mention that death from poison gas must be unpleasant for mammals of all kinds, not just so-called human beings, but, on the occasion of the phone-free party, I kept this opinion to myself, not wanting to disrupt the conviviality of our friends, and instead simply ventured that capybaras, the large and tolerant buck-toothed creatures from South America, were a rodent that everyone liked and could get behind.

‘I know,’ Sandra said. ‘Our daughter saw one – we try to keep her away from screens but someone showed her a picture of a capybara . . .’

‘Search terms,’ Doug/Rob – or maybe it was Tom? – weirdly muttered.

‘. . . and from, like, that day,’ Sandra went on, ‘all she could think of was that she wants a stuffed capybara.’

‘A plush toy,’ Christopher clarified. ‘No taxidermy.’

‘And it turns out,’ Sandra said, ‘they just don’t make them! No capybara plush toys! You can’t even order one from Ecuador or wherever. Not even Peru!’

Things seemed to be going pretty well, I thought, here you had a cheerful, facetious, and occasionally informative discussion of a variety of rodents that would no doubt soon turn into a similarly cheerful, facetious, and occasionally informative discussion of some unrelated topic or other, and then another topic, until the sun started going down, and beyond, with everyone having a pretty good time at our New Year’s Day party, when it occurred to me that I genuinely – and without even having had a drink, let alone taken any drugs – didn’t know what year it was, neither what year had just ended last night nor what year it had already started being today, I mean I knew of course that it had to be two thousand and twenty-something, with the last two digits in the lower or middle twenties, but I didn’t know what the precise number was, or if we were in the midst of the first or second term of President Biden or Trump, and therefore I thought: Something is happening to me, something not good, to my brain, and at the same time had the chance to wonder, with a neutrality barely even laced with melancholy, whether my wife Helen might be right now enjoying herself in a sexual or at least physical, perhaps cuddle-puddle (to use the archaic term) sort of way, as obviously she had every right to do, especially when her husband was mildly afflicted from day to day with an increasingly immedicable depression.

Something I try to do on the last weekend of each month is to sweep the pine needles off the flat roof over our living room, otherwise the gutters and drains get clogged, and so on New Year’s Day my green fiberglass ladder was still leaning up against the house and visible outside the living-room window, and, without knowing exactly why I needed to get away from the eight or nine chattering friends hanging out in our living room and listening to Boards of Canada, now the B-side of the record, I excused myself to go outside and climb up the ladder to the flat roof above the living room, and, once I was up there, sober as a church mouse while everyone else was either tripping or rolling or buzzed on a Bloody Mary or Maria, I grabbed the nylon rope attached with a carabiner to the chimney over the living room and heaved myself up onto the smaller roof over the older portion of the house, with its steep eaves and tar shingles, and it was then that I saw the enormous and gathering cloud of smoke pouring toward us from the east, over the suburban tracts of ranch houses and bungalows and other low-slung dwellings, despite the speed of the wind the huge cloud was unfurling toward us with an almost stately motion, the sound of sirens in the air seemed meanwhile to confirm the reality of this terrible sight, although upon hearing the sirens I felt sure that I’d already been hearing their distributed wailing sounds for some time.

Instinctively I took out my phone and, after magnifying the picture to three times its ordinary size, started filming the advancing cloud of smoke until it occurred to me, as I looked through my phone at this oncoming spectacle, that I’d signed up for Cheyenne County’s free disaster notification service and, in fact, once I’d momentarily lowered the phone and taken it off airplane mode, there it was, a text message from the county government ordering my and Helen’s neighborhood to be evacuated due to a rapidly growing wildfire, of course upon seeing the message I googled the word wildfire and the name of our city, and saw that the local paper, recently purchased by a private equity firm, still employed at least enough journalists as to be reporting on the large blaze, driven by the exceedingly high and unseasonable winds of the day, that had begun in the plains to the east and already consumed an unknown number of structures on the edge of town.

Nothing could have been clearer at the moment than that it was my immediate responsibility, as a sober person with a phone, to clamber back down the ladder and let everyone know, in the living room or anywhere else they might be, that an evacuation order had been issued for our neighborhood and perhaps also for theirs, unfortunately we all had to clear out of the house and people should return right away to their own homes if need be to fetch their animals and/or children and/or elderly parents, I, being sober, could drive anyone who wasn’t able to drive him- or herself, things were going to be okay but we had to leave now, the trouble, however, up there on the roof, with the sun already going down at three in the afternoon, was that some strange mood of calmness, accompanied by what was almost a feeling of satisfaction, almost some species of fulfillment, came over me as I stood there, and for more than two and a half long minutes (I still have the video on my phone) I simply stood still and recorded the boiling wall of advancing smoke inside of which, before too long, flames were visible as well, I seem while I stood there to have experienced the sensation that my small life was no longer a sidelined phenomenon while some planetary juggernaut rolled on, some part of me, that is, seems to have been glad and even gratified to be directly in the line of approaching danger, and anyway I couldn’t just yet rappel down the roof holding the nylon rope, I couldn’t yet go and climb down the ladder, instead I just stayed on the roof and filmed the approaching smoke and flames with my phone until I heard a voice from our yard (it was Charlie’s, male Charlie’s) calling my name and demanding to know dude where are you?

Once I was back in the living room everyone was naturally demanding to know what was up with all the sirens and wanting me urgently to give them back their phones, everyone soon seemed to be gathered around me in the bedroom, waiting for me to unlock the trunk, as I explained to them that I’d received an evacuation order for the neighborhood.

‘Wait what caused the fire man?’ male Charlie wanted to know.

Someone said: ‘Fucking powerlines . . .’ and plausibly enough cursed the local utility.

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘Maybe dry grass. It’s been very dry,’ as a regular visitor to the US Drought Monitor website, I knew that our region had been deeply in drought for months.

The nightmare of any cautious man must be to have been somehow totally reckless behind his own back, and it emerged, as everyone hovered around me and my locked wooden trunk, demanding their phones back so they could reach their children or elderly parents or neighbors, or simply so they could access the breaking news, that I couldn’t find the little brass key to the lock on the trunk, I truly couldn’t seem to find the key to the thing at all.

‘I can’t find the key,’ I said, I was glad that Helen wasn’t present to witness this incomprehensible failure.

‘What the fuck dude?’ tall looming Charlie the man was asking me.

I felt that I knew I’d put the key in the breast pocket of my stupid puffer jacket, it seemed to me that I could see in my memory the gesture of my having done so, but there was no key to be found either in that pocket or in any other pocket I had on my person, nor when I rushed to the kitchen could I find the vanished key on the corner of the counter where I also had a – contradictory – picture of my having left it, very strangely in the months since the fire I’ve also been haunted by a confabulated image of the fugitive brass key falling off of me, out of a breast pocket on some shirt I don’t own, as I climb head first down the ladder from the roof, something I know I never did or even, physically, could possibly do.

‘I have an axe,’ I said to the group and ran off to the carport, the truth was I’d bought an axe some time ago to split firewood before realizing that this task was more difficult and dangerous than I’d anticipated and then learning I could instead buy firewood already split into the correct size for our efficient little wood-burning stove, anyway upon my return to the bedroom I started hacking away at the trunk.

‘Let me take that,’ large well-built Alex said, he grabbed the scarcely used axe from my hands, and with three or four slow, practiced blows he split open the dark wood of the trunk, everyone was soon grabbing their phone from the ruined thing like so many starving people straining after thrown rations in a video clip.

In the upstairs bedroom I found Helen alone and weeping with all her clothes on, she seemed strangely unsurprised to see me arrive with Harriet the cat in her carrier and one go-bag on my back, the other, Helen’s, in my hands.

‘The roads are jammed,’ I said. ‘The streets . . .’ I was referring to the frozen traffic. ‘We have to go on foot.’

She nodded as if to confirm this was only something she already knew, and in a minute she had on her ski jacket and warmest wool hat as we walked very quickly, with some of our friends and many of our neighbors, some of whom we’d never seen before, or maybe these were only visitors, down the sidewalks sloping toward the creek, past countless stalled honking cars as we went.

‘I’m on drugs,’ Helen said, it sounded pitifully factual.

‘I know,’ I said.

‘I don’t have my gloves,’ she said.

‘Here take mine.’

‘But then you don’t have yours.’

Harriet the cat was meanwhile crying continuously inside her carrier.

‘She’s so afraid,’ Helen said, like a child.

My culpability in the disaster was established by the recording I’d made on the roof.

Downstairs in the bedroom, before the other phones were recovered from the trunk, I’d handed over my phone to female Charlie, telling her the passcode, and I guess the camera app was still open and so she saw the video I’d taken up there and sent it to herself (of course I had her as a contact in my phone – and still do), by the next day if not before she had already forwarded the telltale video to most of her fellow partygoers, not to mention other concerned and outraged people.

Nobody we or our friends knew were among the three people who died in the fire, but the Charlies’ house was one of the hundred and then some that were destroyed by what’s since been called the second most destructive wildfire in state history, and another thing I have to admit, there is no way around it, is that the Charlies’ dog, the Great Dane, was inside their house when it burned, one can only hope that August died of smoke inhalation before the flames could reach him.

The question of course is whether the three minutes I spent on the roof, plus the maybe four it took to break apart the trunk with an axe and recover everyone’s phone, would have been enough to allow the Charlies to make it home before all the streets were choked and save their dog, or whether they could at least have called a neighbor in time to ask him or her to rescue August, whether that would have made a decisive difference, and in this context naturally it would have been gauche and insensitive of me to insist to the Charlies: But didn’t you tell us you’d hire a dog-sitter? and when I reminded Helen of this overlooked piece of our late-November dinner-party conversation, saying ‘But didn’t they tell us they’d hire a dog-sitter?’ she simply looked at me and blinked.

About two weeks after the fire, female Charlie emailed me and said she doubted the extra minutes would have really mattered in the end and that I shouldn’t feel bad, in fact she was the person who ought to feel bad, she went on, for sending around my video from the roof to so many of our friends and blaming me for the wasted interval, in reply I wrote back saying of course I understood her passing around the video, everyone is curious about a disaster, I added that Helen and I hoped to see her and the other Charlie soon and I told her that in spite of her graciousness I would always regret the moments I’d squandered during which she and her husband might have called a neighbor, I said too that I couldn’t imagine what it was like to have lost a home as well as a beloved animal and that both Charlies should come stay in our guest bedroom for as long as they liked if this might be convenient for them, of course it doesn’t surprise or affront me that I never heard back from either Charlie or from most of the friends who attended our New Year’s Day party, it doesn’t surprise me either that Helen has hardly touched me since we returned to our intact house late at night on the day of the fire, nothing can justify my extra minutes on the roof, nor do I know what happened to the key, instead I feel myself to have descended head first down the ladder and watched in slow motion as the brass key to the wooden trunk containing all the phones tumbled out of my pocket, even though I know as certainly as any scientist believes in his findings that this can’t have been the case.

‘You don’t have any idea what happened to the key?’ I asked Helen the other day.

‘How dare you,’ she said.

I also have another image, of my responding for some reason to the initial sight of an advancing war zone-sized cloud of smoke by throwing the key off the roof into our back garden, with its wintry deadheaded flowers and accidental mulch of pine needles and ragged patches of stale snow, but this too I know to be false, even though I’ve spent hours by now looking in just the spot where, according to this image, the key must have fallen.

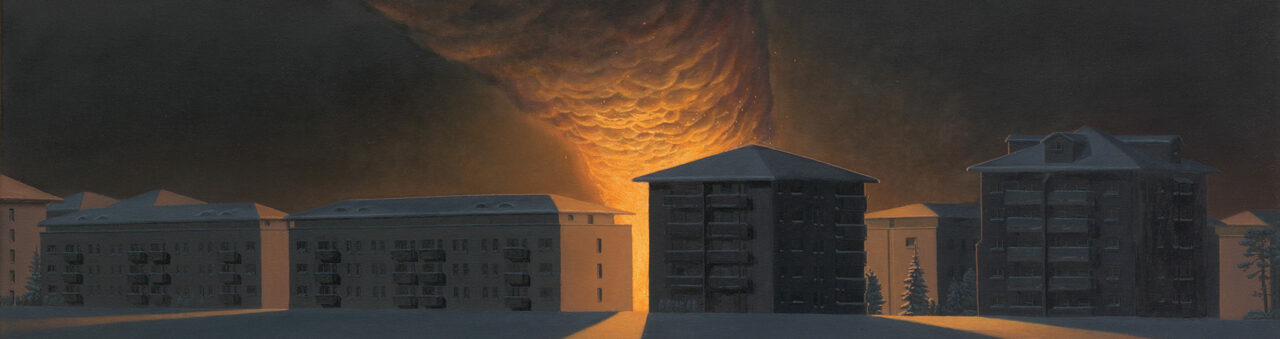

Artwork by Markus Matthias Krüger, Winterdrama #8, 2009

Courtesy of Galerie Schwind