For decades, the medical community has wrestled with the role of race in research and practice, a tug-of-war steeped in historical, social, and political entanglements. While some argue for discarding race, in doing so, we overlook the nuanced interplay between genetics and lived experiences. Does race carry explanatory power, or are there better alternatives to this surrogate?

Race presents a complex interplay of benefits and challenges as a variable in health care studies and clinical practice. But before dropping race as a variable, perhaps we should consider its relevance and alternatives.

Through the lens of medicine, we are, as individuals, an uneven, dynamically changing, hopelessly static admixture of genes, their expression, and the impact of our “lived experience.” Public or population health epidemiology is even more unequal, interacting aggregates of those individuals. For several centuries, we have asked one word, race, to provide an explanatory power for describing our individual and collective health. That is a lot to lift for one word, and unsurprisingly, it has been an abysmal failure.

Race has been, like gender, an original proxy or biomarker, serving to explain our differences. Characterizing race is fluid. While self-reporting of race is found to be more precise than observation, a study of the U.S. Census showed that roughly 6 percent of respondents reported a different race or ethnicity between 2000 and 2010. Racial self-identity can differ over concerns of harms or benefits from disclosure, making it an unreliable biomarker.

When the Human Genome Project demonstrated that humans are genetically 99.5 percent the same, race as a biomarker lost any remaining biological credibility. As a proxy for our lived experience, the social determinants of health race, has lost some of its power to explain as upward and downward mobility has mixed our castes.

Mendel’s peas and family trees

Caste, describing a hereditary structuring of society based on social status and a ritualized measure of “purity,” is an infrequently used description of Western society. Like race, it is asked to do a great deal of explanatory lifting, but unlike race, it better captures the lived experience. Today’s medical forms have found a fellow traveler for race and ethnicity.

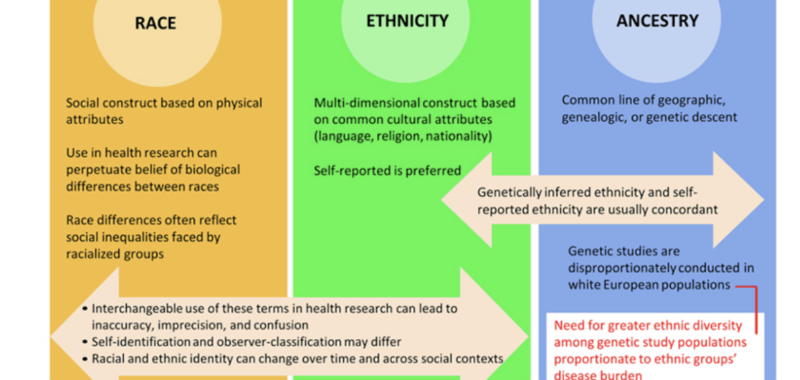

If race is too implicitly biological, ethnicity serves as the counterbalance. Ethnicity offers a broader perspective than race encompasses language, religious and dietary practices, and nationality. To the extent that an ethnic group has been geographically and genetically isolated from its surroundings, it carries specific biological (genetic) and social determinant information.

A third categorization, ancestry, seemingly provides more biologically sound information. Ancestry traces our heritage through family or genetic trees, creating those simplified diagrams we associate with Mendel and his experiments with peas. Genealogic ancestry is based upon our direct ancestors. The child’s genealogic ancestry is an equal combination of their mother and father. Mendel’s experiments with peas affix experimentally derived numbers to those combinations.

Kith and kin have been with us long before Mendel, so genealogical ancestry has deep cultural and legal roots. Patrilineality traces kinship, including rights and “character” through the father. It is found in the Bible and used in agnatic succession to prioritize a male heir to the throne. Matrilineality traces kinship through the mother, e.g., the child of a Jewish “mixed” marriage is considered ethnically Jewish but only religiously Jewish if the mother is Jewish

A more pernicious example comes from America’s legal history, the concept and application of hypodescent, or the one-drop rule, to categorize the offspring of a mixed marriage.

“[Hypodescent] automatically assigns the child of a mixed union between different socioeconomic or ethnic groups to the groups with the lower status, regardless of proportion on ancestry in different groups.”

It is why children of enslaved mothers were considered enslaved and forms the basis of Jim Crow laws. It was officially adopted by the 1930 U.S. Census and was even cited by Halle Barry in a bitter custody battle. The “logic” underlying the one-drop theory relates to our disgust and contamination experience. It lives on in many of our attitudes outside of race, for example, the “contamination” and disgust with foods from GMO or ultra-processed technologies.

However, we have learned much since Mendel. Genetic recombination and independent assortment can and will alter the numeric values we assign from genealogical ancestry. Genetic ancestry only reflects the genetic markers we retain. Moreover, the expression of those genes is impacted by our parental and current environment. Epigenetic changes have been documented in Holocaust survivors and their children, as well as children and mothers from 911. Life experience impacts genetic expression and “may supersede biological ancestry in significance.”

The bottom line is that no one term, race, ethnicity, or ancestry captures what we seek; each fails in its own way. The ambiguity in meaning and interchangeability in use results in inconsistent interpretations, adding a self-inflicted layer of complexity to medical care and health epidemiology. Some argue that these terms must no longer be used; John Ionnadis, among others, suggests, “The call to entirely abandon race from medical research endeavors began several decades ago but is a simplistic solution to a complex set of concerns.”

What might take the place of race?

To understand biological factors, genetic ancestry may be a replacement – although its presumptive granularity and utility are not wholly realized. Better, not best. For explanatory sociologic factors, there are many readily identified factors to capture these impacts better, e.g., access to care, health insurance, income, and health behaviors. Unfortunately, these measures, while “probably closer to causal relationships than race,” are binary or quantified, losing nuance. For example, health insurance may not be a measure of “access to care.” given the friction points of out-of-pocket financial or time expenditures and limitations to formularies of readily available drugs and treatments.

For clinicians, those actually providing care, the racism of race may be academic navel-gazing. Race and its synonyms can provide meaningful insight into diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic clinical tools. Diseases with strong genetic underpinning, such as sickle cell disease, have solid diagnostic associations with race. A similar genetic disease, thalassemia, has a strong ethnic association. Thalassemia can be divided into an alpha form that primarily impacts the Jewish ethnicity of Europe and a beta form that affects Jewish ethnicity from the Mediterranean, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Much academic and media furor has come from studies demonstrating that the “standard” means of assessing renal function using serum creatinine was systematically underestimating lower levels of renal function in Blacks. This was due to an unwarranted assumption about their baseline muscle mass, the source of creatinine. As stated in a 2023 review, “A race-stratified [creatinine clearance] (i.e., separate equations for Blacks and non-Blacks) would provide the least biased [creatinine clearance] for both Blacks and non-Blacks and the best medical treatment for all patients.”

Pulmonary function tests have incorporated adjustments for race based on observational data from the 1999 NHANES survey involving Whites, Blacks, and “Mexican Americans.” Subsequent studies questioned these adjustments and found that “Black individuals were shown to have a significantly higher prevalence and severity of lung disease” in race-neutral formulas.

Race and its synonyms have a role in some situations, in others, some incremental values, and in others, it is obsolete. In some instances, what we see today as racism is posited as the proximate cause of these erroneous conceptions. Considerations of intent, especially for historical situations, do little more than remind us of our fallibility. The beauty of science lies in its ability to self-correct.

No single term—race, ethnicity, or ancestry—adequately captures the complexities of human health. Rather than abandoning these terms outright, a nuanced approach that considers the specific contexts in which they are used might offer a better path forward. The challenge lies not in discarding race but in understanding its limitations and finding the most effective ways to address them in our pursuit of better health outcomes.

Charles Dinerstein is a surgeon.