There’s a scene in “Megalopolis” where the visionary architect Cesar (Adam Driver) shares a kiss with Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel) atop construction rafters hanging high above the city of New Rome — and time stops.

When he first saw it, composer Osvaldo Golijov assumed writer-director Francis Ford Coppola staged it like that just to be original. He inquired why the kiss was set a thousand feet above the ground, and Coppola explained: “Because a kiss is a very dangerous thing. You may think you have all your life figured out, but a kiss can make everything crumble.”

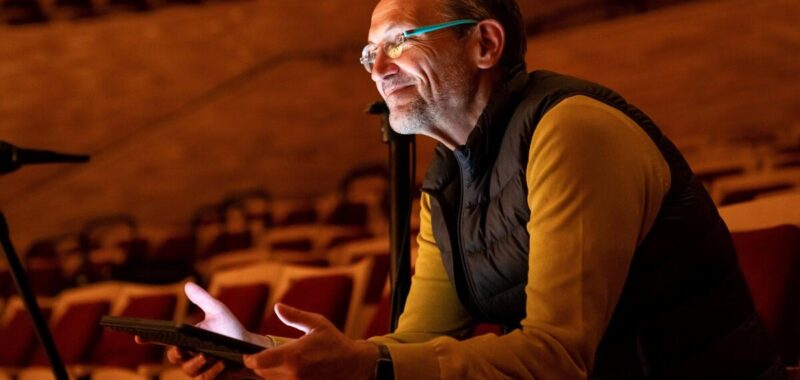

“So he has a reason for everything,” says a visibly delighted Golijov, who answered Coppola’s call for that scene by writing a shimmering, surging love theme. “That’s why I chose that orchestration that is very what I call ‘aerial,’ and Wagnerian, and kind of also Hollywood — which I never knew that I could do.”

Music has always been a passion for Coppola, whose childhood was marinated in opera and whose composer father often contributed to his films. From the melodic Sicilian ghosts of “The Godfather” by composer Nino Rota to the aching Eastern European love theme in “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” by Wojciech Kilar, his stories ooze with musical expression.

“When my father, Carmine, died, I lost a classical composer I used to collaborate with since I began directing plays in college,” Coppola says via email. He wanted a Polish classical composer for “Dracula” and approached Witold Lutosławski — who told Coppola it would take him five years to compose the amount of score required. So instead he went to Kilar, “who did great but gave me very little music, albeit fine, which required lots of reuse and remixing of cues.”

“Still in need of a ‘classical’-type composer,” Coppola approached the American maestro John Adams, “who was kind and receptive but not really interested in composing new music for me.” An acquaintance gave Coppola a list of five newish concert composers to check out, including Thomas Adès and the Argentina-born Golijov. Coppola was very attracted to the latter’s work, particularly his monumental piece, “La Pasión Según San Marcos.”

“I felt his music was complex, beautiful, harmonically and textually varied,” says Coppola, “and interesting.”

Coppola first reached out to Golijov 20 years ago and invited the composer to his home in Napa to discuss “Megalopolis.” The filmmaker had been dreaming of this “New Roman” epic since the 1980s, and he asked Golijov to write a tone poem based on the script, something in a “muscular, American, midcentury idiom,” says Olijov, “a kind of industrial, mechanical thing.”

That iteration of the film stalled, and in the meantime Golijov scored Coppola’s “Youth Without Youth,” “Tetro” and “Twixt.” Finally, after Coppola sold part of his wine business to finance his passion project, “Megalopolis” was reborn.

Gone was any talk of industrial midcentury music. When Golijov visited the set in Atlanta last year, Coppola — who hadn’t seen the composer in 12 years — stopped what he was shooting and blurted out: “Osvaldo, we need a big love theme!”

Golijov laughs at the memory: “He didn’t even say, ‘Hi.’ He said, ‘This is the theme that will hook people in, and then they will come again to the movie for the other layers.’”

Coppola specifically requested a classical love theme, “but geometric,” which Golijov interpreted as “an architectural theme that is just four notes, and then you can do whatever you want.”

So Golijov came up with a simple, pining leitmotif that he then reconstituted into many different guises throughout the score: It’s blue and jazzy on saxophone as Cesar roams the city streets at night, slow and drugged when he’s in a similar state.

Like the film itself, Golijov’s score is wildly eclectic and constantly referencing old cinema. It pays homage to classic Hollywood scores about ancient Rome, namely Miklós Rózsa’s “Ben-Hur,” with brass fanfares and stately processionals. There are homages to the work of Bernard Herrmann, with music for eely low winds (Coppola told Golijov, “When in doubt, go to Hitchcock”).

The score also plays on the concept of time and uses electronic manipulation for ticking, grooving rhythmic passages. It swings from one extreme to another, matching Coppola’s grandiose gestures toward futurism, ancient history, symbolism, theatrical performance — and, at the heart of it all, love.

“I told him I wanted the music to be something audiences could dance to,” Coppola says.

The director’s love of opera is what makes sense of this huge, heaving epic. Giancarlo Esposito, who plays Mayor Cicero in the film, also grew up in a house of opera: His mother was a Black opera singer from Alabama who met his Italian father while performing in Naples.

The actor, who first worked with Coppola on “The Cotton Club” 40 years ago, says he sees Coppola as “this deeply Italian man who, in some ways, resembled my father. I don’t think I’ve ever told him that.”

Esposito considers “Megalopolis” to be about “art imitating life and history repeating itself.” He adds of Coppola: “Of course he would put a very operatic soundtrack on this film, because it’s what it deserves. In fact, it’s what it’s calling for. It’s what it demands.”