Eboni K. Williams doesn’t give a damn about rules. She never has. She played by her own rules when she finished high school at age 16 and became a first-generation college graduate. She played by her own rules when she left her stable law career to pursue TV journalism. And when she took a job at Fox News, despite disagreeing with some of the network’s politics. And when she joined Bravo’s The Real Housewives of New York City, becoming the first Black cast member on the series.

“Beating odds, beating statistics — shattering stereotypes has always been very important to me,” she says. So when she decided to become a mom, of course she had to do it her way, on her timeline. And as she embarked on single parenthood, she noticed she wasn’t the only Black woman publicly modeling how to have kids on your own terms, either.

There’s her fellow Housewives alum Candiace Dillard Bassett, who opened up about her IVF journey during her time on The Real Housewives of Potomac — a reminder that fertility journeys can look different for everyone. There’s singer Ashanti, who married rapper Nelly while pregnant with their first child — proof that you can check off life’s milestones (or not!) in whatever order you please. And there’s countless other women, from Gabrielle Union to Kandi Burruss to Naomi Campbell, who have expanded their families through stepparenting and surrogacy — exemplifying how becoming a mother doesn’t have to look a certain way.

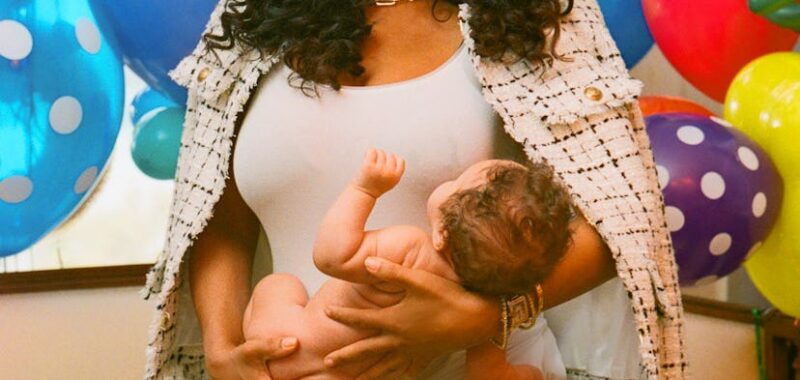

Now, by sharing her life with baby Liberty, born in August, Williams wants to add to the possibilities for women like her. “Part of my intention with everything I do, but especially this part of my life and this journey, is to challenge social and cultural norms as they relate to Black women, Black mothers, and single Black mothers,” she says. “Those are three constructs that I hold with fragility. I don’t by any stretch think that I am singular in my ability to take on this work. But I do see myself as positioned well to challenge how those things are seen and how they will be seen going forward.”

“I know me well, and I don’t like group projects. I enjoy the freedom of being the executive decision maker.”

Williams and I are chatting via Zoom on Election Day. We’re waiting to find out whether this country would choose to be led by someone who looks like us — even though we pretty much already knew the answer. Yet despite the weight of the political atmosphere, the conversation flows easily. We finish each other’s sentences and laugh heartily in a way that feels familial. In addition to both being girl moms, we learn we’re both members of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Inc., the historically Black Greek organization that counts Vice President Kamala Harris as one of its own, too. Williams is even wearing pink and green, the sorority’s colors; Liberty is strapped to her chest, sleeping peacefully. I ask with the sincerity of one mom to another: How are you?

“All — with a little asterisk — is well,” she says.

The 41-year-old is at the tail end of the fourth trimester, and she’s still getting used to her new identity as a parent. “I was never one of those girls or women who always had a motherhood fantasy,” she says, in the strong, steady voice of someone who was born to be on TV. Her professional identity came more naturally. She froze her eggs at age 34, but not because she was seriously thinking about having children with her then-partner, or even having children at all. “I did that as a flex,” she says, laughing. “This was not very different for me than buying a Birkin bag. It was a power move.” The power of saying: I have options.

But something shifted for Williams during the pandemic. She’d already been married and divorced once, and in August 2020, she ended her engagement to businessman Steven Glenn. Meanwhile, with her therapist’s encouragement, she tracked down her biological father; the two had a 10-minute conversation, in which he acknowledged paternity but requested no further relationship. For many women, and for even more Black women, these circumstances — the lack of a partner, fractured family relationships — would steer them away from parenthood. For Williams, they pulled her toward it. About 18 months later, she decided to pursue conceiving a child via in vitro fertilization.

“I really am a moth drawn to a fire.”

It started with discovering a group on social media called Single Mothers by Choice. “It didn’t occur to me,” she says. “Like most, when I heard ‘single mom,’ I thought tragic. I thought poverty. I thought, ‘Your child will end up in jail and a menace to society.’” But the more she researched, the more having a child on her own not only presented itself as a potential option, it became the preferred option. “I know me well, and I don’t like group projects,” she says with a laugh. “I enjoy the responsibility and the freedom of being the executive decision maker. I kind of need to have full authority and move how I see best.”

This comes as no surprise to friends like Natalie Robinson, an AKA soror who’s known Williams for a decade and has been by her side on her path to motherhood. “Eboni is the ultimate risk-taker and go-getter — someone who’s always thinking ahead, full of ideas, and ready to dive in. I can always count on her to pull up her Notes app and share her next big plan,” Robinson says. “If she’s thinking about something, she’s probably already made up her mind, but she still values my perspective and wants to hear my thoughts.”

Williams was also inspired by the way women in the group weren’t closing the door on love. So many Black women have been told both by their mothers and the media that they have to choose their priorities — like marriage or career. But the group made it clear that having a child on her own didn’t mean she had to give up on finding a partner. Says Williams: “This was this wild-card scenario that said, ‘What if I told you you could get the financial [stability], and you could still get the motherhood piece, and it doesn’t mean you’re totally erasing the possibility of the love story?’”

In a way, her choice to move forward with the process wasn’t dissimilar to other big life decisions she’s made, whether taking a job at Fox News or becoming a Housewife.

“I really am a moth drawn to a fire,” she says. “I felt called to do the work of redefining that, of disrupting that. I saw this choice as consistent with my calling — to do the thing I’m not supposed to do.”

IVF can feel like a game of roulette, and it worked for Williams on her first try: She had one egg, resulting in one healthy embryo, and one successful transfer resulting in conception. “I personally take issue with high-profile celebrities that use their platform to tell half of their fertility story,” she says. “That’s one reason why I’m so transparent. We need to be honest about the likelihood, and we need to be honest about the complications.”

Williams administered the shots to herself — when it comes to pain, as she puts it, “I ain’t no punk” — and had it not been for her college bestie who insisted on staying in town, she would’ve labored and given birth alone, by choice. She was comfortable with the care team she assembled; her OB-GYN and doula were both Black women. But she was still mindful of any medical intervention that she felt might have been more in the hospital’s best interest than in hers or her daughter’s. After Williams was induced and 45 hours of labor, Liberty Alexandria Williams was born on Aug. 13.

“I [froze my eggs] as a flex. This was not very different for me than buying a Birkin bag. It was a power move.”

Williams shared the significance of Liberty’s name in an Instagram post, recounting the origin of the Statue of Liberty as a tribute to formerly enslaved Black Americans. She tells me the name is an invitation to her daughter to live an unrestricted life, to exercise the freedom bestowed upon her. “I brought her into a world where she is free,” she says. “Her ability to remain free will be her work.”

The transition to motherhood hasn’t come without challenges. Williams acknowledges that she’s struggling with some postpartum body changes. “But I know enough and have lived long enough to know if that is one of my top challenges, I am abundantly blessed,” she says laughing. She hired a night nurse to help out five days a week and — despite her no-group-projects mentality — has leaned on her inner circle. “What’s truly special is her trust in her village,” Robinson says. “She’s not overbearing but instead embraces the support around her, knowing it takes a community to raise a child. Watching her in this role has been nothing short of inspiring.”

The biggest adjustment for Williams, though, has been a new sense of self. Growing up, Williams watched her grandmother Katie care for white children while Williams’ mother worked and built her business. “Caregiver” and “breadwinner” were separate jobs — and Williams, as a Black woman who has worked to sit at tables where women before her couldn’t, is still learning how to integrate both. “God forced me to encounter this identity conflict and crisis,” she says. “[I’ve] done the thing that I wanted to do on my terms, which is like the ultimate boss move on one level. And on the other level, I still somehow someway ended up as the help. And it was really, really hard for me the first several weeks.”

Williams found solace in one of her favorite movies: Gone with the Wind. She closely watched Hattie McDaniel’s Mammy character — the role McDaniel made history with, becoming the first Black actor to win an Oscar. “I really started to unpack the narrative that although she was the ultimate help, Mammy was also the biggest boss in the house,” Williams says. “She was the one that was most in control and most in charge.”

More changes are in store. Liberty will soon be in a language-immersion day care three days a week. Williams put her Harlem home up for sale this summer. (As if moving in New York City isn’t hard enough without a newborn.) It’s a whole new season of Eboni, and she’s greeting it with open arms. Her life didn’t need to look a certain way to become a mom — why start following the rules now? She can date without the burden of finding a co-parent; she can mix parenting life and her professional life in ways she hasn’t even seen yet. Liberty has, in fact, liberated her mother.

“I don’t want to inadvertently limit who I get to be,” she says. “I’m wide open to the element of surprise. Let God surprise me. Show me something!”

Photographs by Jason Rodgers

Set Designer: Maisie Sattler

Hair & Makeup: T. Cooper

Talent Bookings: Special Projects

Production: Kiara Brown

Associate Director, Photo & Bookings: Jackie Ladner

Editor in Chief: Kate Auletta

SVP Fashion: Tiffany Reid

SVP Creative: Karen Hibbert